Recent UK researches has revealed that Oxford - AstraZeneca vaccines have sucessfully slowed down the spread of Coronavirus, ather than simply preventing symptomatic infections.

The rate of positive PCR tests declined by about half after two doses, according to preliminary results by researchers at the University of Oxford that have yet to be peer reviewed.

Their analysis, released as a preprint Tuesday, also supports spacing out doses and estimates good efficacy after just one shot of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, according to CNN.

The study did not measure transmission directly -- for example, by tracing contacts who were infected by study volunteers. But the researchers did collect regular nasal swabs from some participants and found that the rate of positive PCR tests fell by half after two doses of the vaccine. After one dose only, the rate of positive tests fell by 67%.

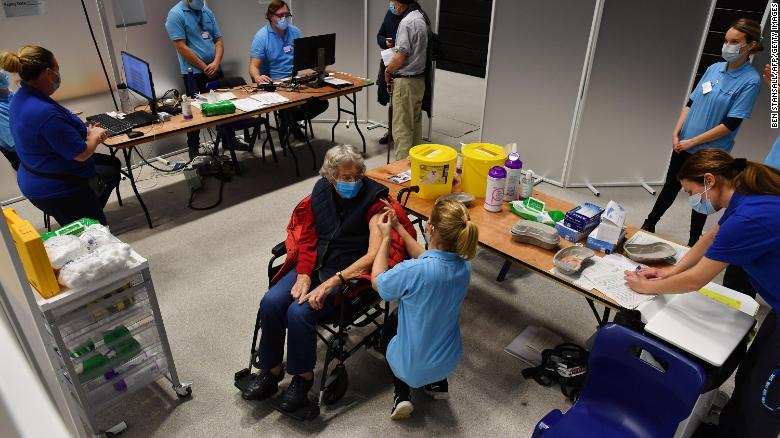

A patient receives an injection of the Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine at a vaccination center in Brighton, southern England, on January 26, 2021. (Photo: CNN)

"While transmission studies per se were not included in the analysis, swabs were obtained from volunteers every week in the UK study, regardless of symptoms, to allow assessment of the overall impact of the vaccine on risk of infection and thus a surrogate for potential onward transmission," the authors write.

If the vaccine were simply making infections milder, PCR positivity would not change, the authors argued in the preprint analysis. "A measure of overall PCR positivity is appropriate to assess whether there is a reduction in the burden of infection."

Coronavirus vaccine trials have primarily looked at prevention of symptomatic cases of Covid-19. Previously, there has been little other public data suggesting that vaccines could prevent people from passing the infection to others.

Speaking to the UK's Science Media Centre (SMC), Helen Fletcher, professor of immunology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said the data in the study "suggest a possibility that the vaccine could have an impact on transmission but further follow-up would be needed to confirm this."

Dr. Doug Brown, chief executive of the British Society for Immunology, told the SMC the study "hints that the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine may be effective in stopping people being able to transmit the virus."

According to BBC, the effectiveness of the vaccine increased with a longer gap of 12 weeks before the booster jab.

When the second dose is given, the study found the level of protection from the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine rises to 82%.

In other developments:

One of the world's largest follow-up Covid studies found almost 90% of people who tested positive for Covid had protective antibodies against the virus six months after their initial infection.

The number of people with coronavirus has changed little in the week to 23 January, the Office for National Statistics says, with virus levels still high in England (one in 55) and level in Scotland (one in 110), Wales (one in 70) and Northern Ireland (one in 50).

Study “reassures us”

It is the first time a study has shown a vaccine can reduce the spread of Covid-19 (Photo: Getty Images)

The UK has set itself apart from many other countries by prioritising giving the first dose to as many people as possible, delaying the second jab for about 12 weeks.

The aim is to save more lives by giving some protection to a larger number of people, but the UK has faced criticism from the British Medical Association for following this path with no international support.

Prof Andrew Pollard, chief investigator of the Oxford vaccine trial, said the results supported the UK's approach to delaying the booster shot.

It "reassures us that people are protected from 22 days after a single dose of the vaccine," he says.

The new analysis of the Oxford vaccine suggests that transmission of the virus from those who have been vaccinated could be substantially reduced.

If verified by the scientific review process, it means that as more people get the jab, infection levels could come down faster than they would otherwise and enable the government to lift restrictions sooner than they could otherwise.

One in six of the population has had at least one jab so far.

There's still a long way to go but the impact on case numbers could begin to be felt in the coming weeks.

The fly in the ointment though is the recent emergence in the UK of variants that may be more resistant to some vaccines.

Experts believe that jabs will still offer good protection especially against severe illness, but even so this could slow progress.

The race is now on to vaccinate as many people as quickly as possible, in order to keep a step ahead of the variants.

The government is also trying to slow the spread of variants through enhanced surveillance and testing.

But a critical part of the strategy is to drive down infection levels, so people don't catch the virus in the first place, whatever variant it might be.

"This is positive news as it shows that just one dose of this vaccine generates good levels of immunity and that this protection does not seem to wane in the shorter term," said Brown, of the British Society for Immunology.

"In immunology terms, this finding is not unexpected as we know that some other vaccines confer better immunity when the doses are more spread out. Although further information is required to confirm these findings for older age groups, overall this new research should provide reassurance around the UK's decision to offer the two doses of this vaccine 12 weeks apart."

Professor Azra Ghani, chair in infectious disease epidemiology at Imperial College London, cautioned against interpreting the estimates in the study as indicative of a higher efficacy with a longer dosing gap, citing limitations with the study design.

"Most importantly, the study was not designed to look at different dosing gaps or at one versus two doses. This means that participants weren't randomised and it is therefore quite possible that there are other things that are driving this apparent trend with dosing schedule," she told the SMC.

"The only way in which this question can be answered robustly is in a prospective trial with different dosing schedules compared side-by-side."

Alongside the Oxford vaccine, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is also being rolled out across the UK.

Clinical trials of the Pfizer vaccine and Moderna, which has been approved but is not yet in use, did not look for a potential impact on transmission.

However, BBC health correspondent James Gallagher said the different vaccines all target the same part of the virus so if one can cut transmission, there is a good chance the others can too.

The data from this latest trial was drawn before new variants, including the South Africa one, emerged.

Asked how protective the Oxford vaccine could be against new mutations, Dr Pollard said he was anticipating "good protection" against the Kent variant and would publish details "very soon".

On other variants, he told BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "When we look at the new mutations that have been arising in other countries and now also here in the UK - that is the virus trying to escape from human immunity, and that's whether it's from vaccines or from infection.

"I think that's telling us about what's to come, which is a virus that continues to transmit, but hopefully that will be like other coronaviruses that are around us all the time, which cause colds and mild infections.

"We will have built up enough immunity to prevent the other severe disease that we've been seeing over the last year."

Uncertainty about Oxford vaccines

Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said the extra data in the paper were helpful but that some "inevitable uncertainty" around exact efficacy values remained.

"The data definitely provide some evidence to suggest that the eventual protection from two doses of this vaccine are not worsened by having a longer than 28 or 42 day period between doses and tend to confirm what had been shown before, that if anything the eventual efficacy was better," he said. "The data also do not provide any evidence that efficacy wanes after the first dose."

Similar data is not yet available on delaying the second dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine to 12 weeks after the first dose, said Dr. Gillies O'Bryan-Tear, past chair of policy and communications at the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Medicine in comments to the SMC. But, he added, "most commentators agree that it is likely to be the same with that vaccine, and indeed, other two dose vaccines."

The authors caveat that the trials were not initially designed to evaluate efficacy by dose intervals, but the data "arose due to the logistics of running large-scale clinical trials in a pandemic setting."

The primary analysis is based on 332 symptomatic infections that occurred among more than 17,000 trial volunteers in the UK, Brazil and South Africa more than two weeks after their second dose.

AstraZeneca announced last month it had completed enrollment in its Phase 3 trial in the United States, which will serve as "the primary basis" for the company's eventual application to the US Food and Drug Administration.

The vaccine has already been authorized in a number countries, such as the UK and India, but authorization may not come in the US until late March at the earliest, according to Operation Warp Speed's Moncef Slaoui.

Figures from Tuesday show there were 16,840 new confirmed cases of coronavirus, with the number of new infections dropping 27% since last week.

A further 1,449 people were reported to have died within 28 days of a positive test.

Chau Polly